By Tahir Masood (Rafa’el)

Foreign Correspondent – Ireland

Daily Capital Mail

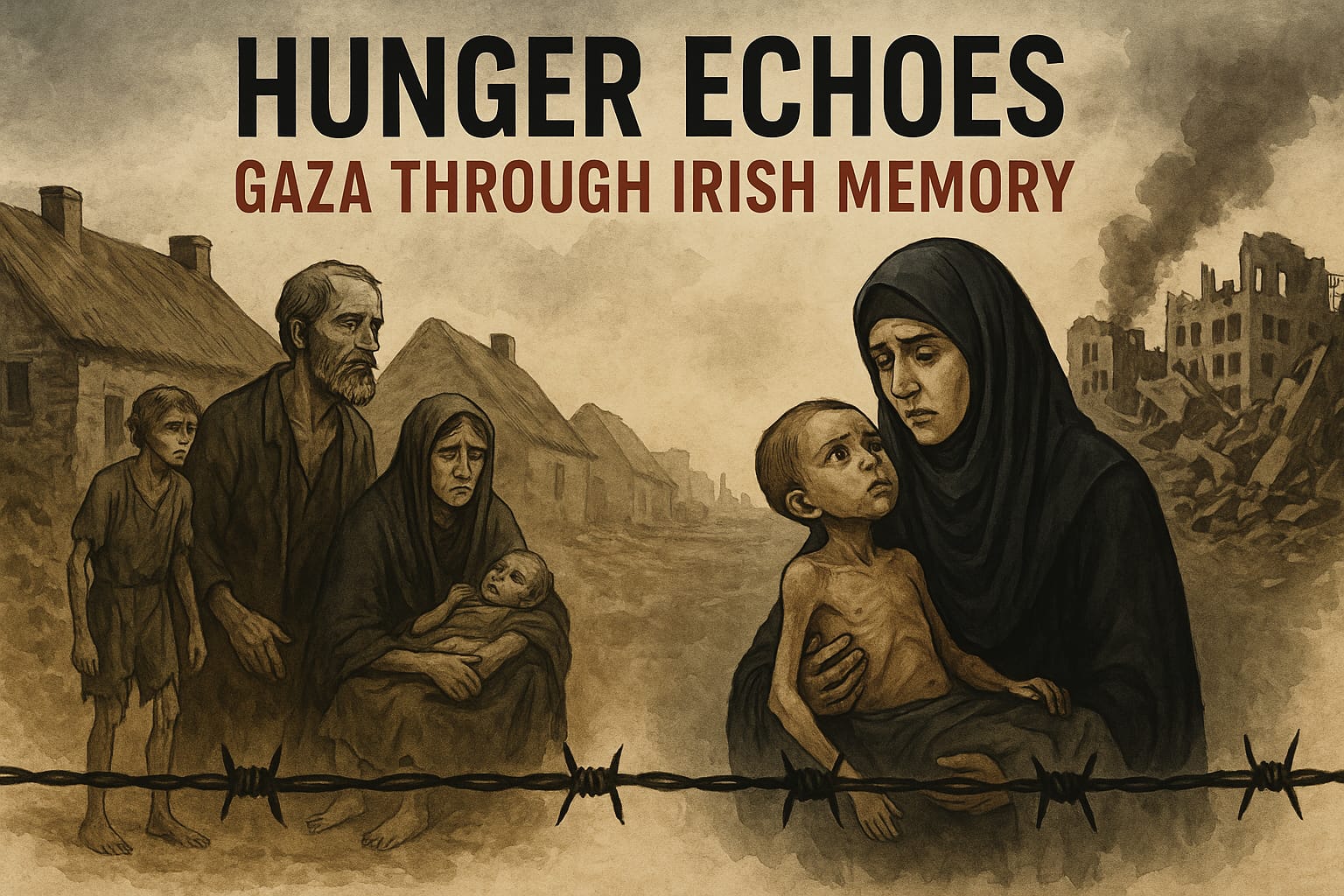

In Gaza, international aid flows far more quickly thanks to modern communications, but the results remain heartbreakingly similar. Well-publicized international pledges have not translated into consistent, safe delivery of aid. Convoys are blocked or bombed, humanitarian workers face unacceptable dangers, and political infighting prevents the establishment of a sustained, protected humanitarian corridor. Social media has ensured the world sees Gaza’s agony in near real time, but so far, the response has failed to match the urgency of the crisis. Children are starving while the international community argues over the legality of the blockade and proportionality of force, leaving ordinary civilians to pay the price for political paralysis. One reason for this repeated failure may be how famine is framed in the public imagination. We still often see famine as a weather-driven tragedy — the result of drought, flood, or blight — rather than as a preventable human-made disaster. This framing allows governments to dodge moral responsibility. During the Irish famine, many British politicians sincerely believed the market would eventually correct itself and that intervening too much would only reward “idleness.”

Similarly, in Gaza, some policy makers rationalise blockades as necessary for security, even while their consequences starve children. When governments see food security as an acceptable bargaining chip, famine becomes a predictable consequence. The consequences of famine are not confined to the immediate loss of life. Famines leave behind scars that run through generations, reshaping cultures, economies, and identities. Ireland’s famine fractured families, emptied villages, and launched one of the greatest waves of emigration the world has ever seen. Irish emigrants carried their trauma across oceans, forming a diaspora that would permanently transform the population of countries like the United States, Canada, and Australia. Songs, stories, and commemorations of the Great Hunger still form a core part of Irish identity, reminding later generations of how a colonial system had failed them. In Gaza, there is no safe place to emigrate, no welcoming shore across the sea. Instead, survivors of the famine conditions remain trapped, unable to rebuild their lives, and subjected to repeated military operations that destroy any attempt at recovery. The psychological wounds of constant hunger, grief, and terror will be inherited by Gaza’s children, shaping how they see the world for decades to come. If trauma passes from generation to generation, then Gaza may be forging a collective memory of victimhood and injustice as powerful as Ireland’s Great Famine legacy. As Irish humanitarian Ann Marie McDonald writes in her reflections on Gaza’s current tragedy, “The Irish famine is more than a story of hunger — it’s a reminder of what happens when the world turns away.” With over two decades of advocacy for the Palestinian cause in Ireland, Ann Marie McDonald has tirelessly linked Ireland’s colonial memory to present-day solidarity, reminding us that empathy is a political force. It is crucial to name what is happening: the suffering in Gaza is not the result of natural forces or isolated conflict — it is the direct consequence of Israel’s long-standing and systematic oppression of the Palestinian people.

The Israeli-imposed blockade, military incursions, and indiscriminate bombing campaigns have devastated Gaza’s infrastructure and made life unbearable for its people. Numerous international human rights organisations and legal scholars have described Israel’s actions as war crimes, and many now warn that the deliberate starvation of a civilian population constitutes a crime against humanity — even genocide. Another disturbing parallel is the pattern of blaming the victims. In the 1840s, British newspapers frequently painted the Irish as backward, lazy, and responsible for their own misfortune. Racist stereotypes of the Irish as drunken and inferior made it easier for politicians to justify minimal relief. Likewise, in today’s political discourse about Gaza, civilians are often held collectively responsible for the actions of militants. By framing the entire population as complicit, policymakers rationalise collective punishment that affects children, women, the sick, and the elderly. History warns that once a group is dehumanised, its suffering becomes easier to ignore. These dehumanising narratives not only kill empathy but also serve to protect the status quo. In Ireland, they allowed a colonial system to maintain power even while its subjects starved. In Gaza, similar narratives protect the political and military apparatuses responsible for the blockade, making real change more difficult. Ending a famine requires shifting these deep prejudices and seeing the affected people first as human beings, with the same right to food, water, shelter, and dignity as any other. In both Ireland and Gaza, foreign governments and their allies have played complex roles, sometimes providing charitable donations while failing to change the root causes of hunger. During the Irish famine, the Ottoman Empire sent money, and even the Choctaw Nation, itself having suffered forced displacement in the Trail of Tears, raised funds for the Irish poor. These acts of solidarity resonate even today, showing how ordinary people can care across oceans and cultures. Yet these gestures, while noble, could not override the British Empire’s deadly indifference. In Gaza, foreign aid has similarly been generous in absolute terms — billions of dollars pledged over the years — but these efforts are repeatedly undermined by policies of siege, blockade, and destruction that make humanitarian work nearly impossible. This points to the most crucial lesson both famines teach us: you cannot fix a politically engineered famine with charity alone. Famine is a political problem requiring a political solution. Humanitarian deliveries are important, but they will never be enough if the conditions of siege, occupation, and colonial-style control persist. It is as true today as it was in 1847 — only structural change can end mass hunger. What does this structural change look like? For Ireland, it eventually meant land reform, partial independence, and a slow dismantling of colonial rule, though it took decades to recover from the loss of population and morale. For Gaza, structural change would mean lifting the blockade, rebuilding its shattered infrastructure, allowing free movement of people and goods, and ending policies of collective punishment. Only then can its population begin to rebuild livelihoods and food security, free from the constant threat of war and starvation. At the heart of famine lies a moral failure: a decision by people with power that some lives are worth less than others. When the British Empire decided it was acceptable to keep exporting Irish grain while Irish peasants died, it made a statement about whose lives mattered. When modern policymakers justify cutting off Gaza’s food supplies to achieve security goals, they make a similarly chilling statement. A famine is not only about empty stomachs but also about a society’s deepest values. It asks: who counts as fully human, worthy of protection? Today, the international community faces a critical test. Will it tolerate a famine in Gaza that has been predicted for months, documented in real time, and broadcast across the world? Or will it mobilise genuine political courage to prevent a repeat of the Irish Great Hunger? Early signs are not encouraging, as diplomatic negotiations drag on while children waste away. But there is still time to intervene — and there is still a chance to be remembered as a generation that did not stand by while history repeated its worst mistakes. Ireland’s experience shows us that famine leaves a legacy that is felt for centuries. The Irish diaspora still tells the stories of ships filled with starving passengers crossing the Atlantic, of landlords evicting families from their homes, of entire villages lost to death and emigration.

Gaza’s children will one day tell stories too — of airstrikes destroying bakeries, of mothers rationing one piece of bread across three children, of aid trucks turned away at military checkpoints. These stories will shape their sense of justice, their hopes, and their relationship with the outside world. Whether those stories end in bitterness or in reconciliation depends on choices the world makes right now. At a deeper level, the parallels between these two famines reveal something fundamental about how power works. Controlling food is one of the oldest methods of controlling people. Whether it is an empire managing its colonies, or a modern state managing an occupied territory, the power to give or withhold food is a terrifyingly effective weapon. Breaking that cycle demands a new kind of politics — one rooted not in domination and suspicion, but in the shared belief that every human being deserves to eat. That should not be a controversial statement, yet in practice it seems the hardest to uphold. As the world watches Gaza today, the question is whether lessons from Ireland’s famine will truly be applied. Historians have shown again and again that mass hunger is preventable when there is political will. Early warning systems, international treaties, and modern technology mean we are better prepared than the Victorians were in the 1840s. There is no excuse for delay. Yet preparedness counts for nothing if the moral will to act is absent. If powerful governments continue to treat Gaza’s children as acceptable collateral damage, then the modern world has no right to congratulate itself on having advanced since the 19th century. In the end, famines are tests of empathy. The British Empire failed that test in Ireland. The international community is now being tested in Gaza. Whether history remembers us as bystanders or protectors depends on whether we are willing to challenge the political structures that use hunger as a weapon. Humanitarian convoys, donations, and emergency food rations all help, but they will not solve the problem if the conditions of siege remain in place. Gaza’s famine, like Ireland’s, is a human-made crisis demanding a human-made solution. If there is one lesson to carry forward, it is that famine is a crime against humanity that implicates us all. Whenever famine happens, it forces every generation to confront what it truly values. Will we look away, as past generations looked away from Ireland’s suffering? Or will we act decisively to uphold the most basic right — the right not to starve? That choice is before us, and history will record how we answered.