Tahir Masood (Rafa’el)

Foreign Correspondent (Ireland)

Turbat, Balochistan – June 2024. A name now etched in blood: Sheetal—also reported as Shakila or Sheetal—was allegedly gunned down by her own brother in what is being described as yet another horrifying honor killing in Pakistan’s restive Balochistan province. Her crime? Marrying a man of her choice.

Turbat, Balochistan – June 2024. A name now etched in blood: Sheetal—also reported as Shakila or Sheetal—was allegedly gunned down by her own brother in what is being described as yet another horrifying honor killing in Pakistan’s restive Balochistan province. Her crime? Marrying a man of her choice.

According to local sources and initial police reports, Sheetal had eloped with her husband, a decision that enraged her family. Days later, she was reportedly murdered in cold blood by her brother, who claimed the act was to restore “family honour.” Her death has triggered a wave of anger and mourning in Turbat and across the region, once again thrusting Pakistan’s systemic failure to protect women into the national spotlight.

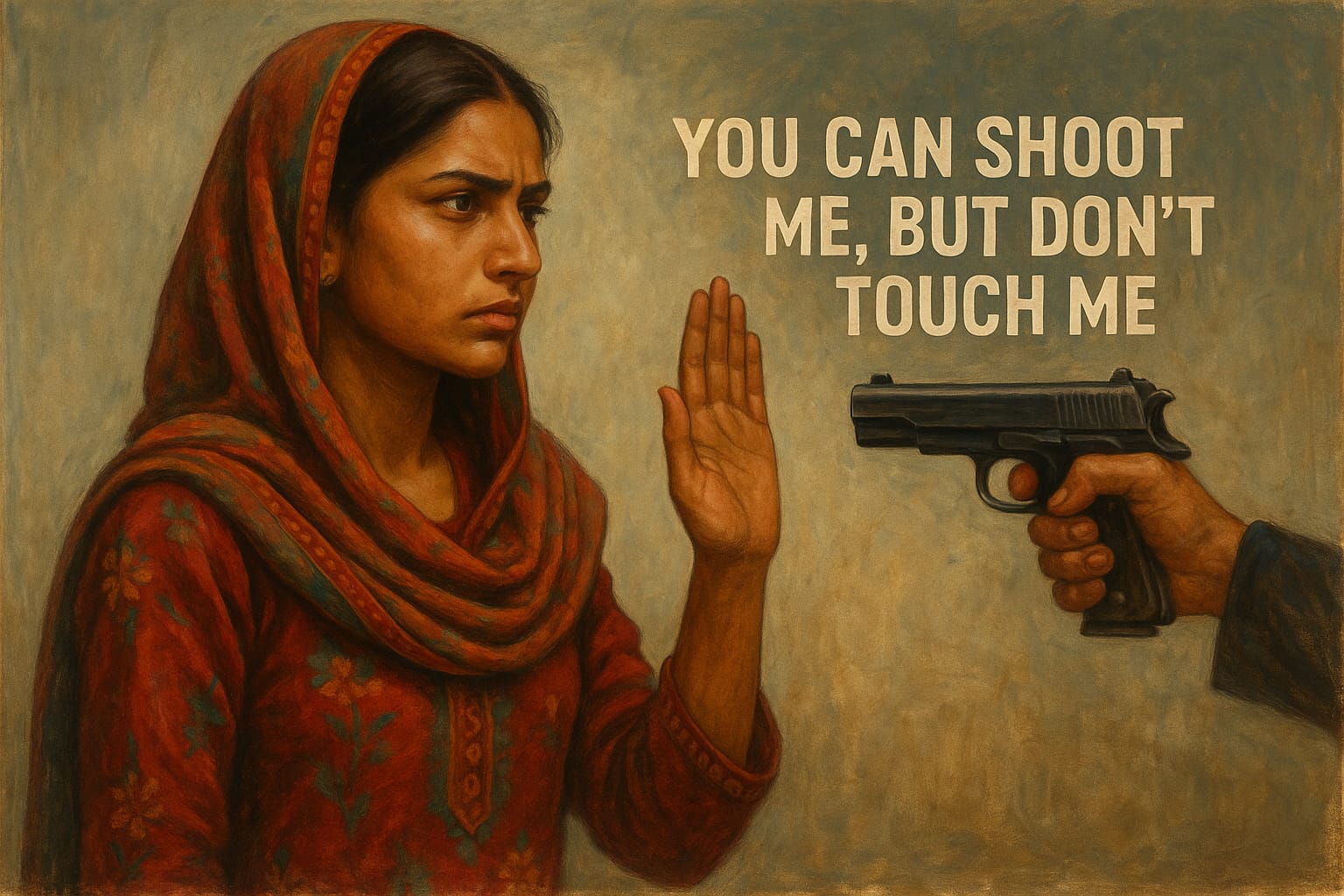

Those close to the case recall that Sheetal remained defiant and fearless until her final breath. Confronted with threats, her voice did not tremble. Witnesses say her last words before being shot were, “You have the right to shoot me, but do not touch my body.” In that one sentence lay the entire tragedy of women like her—strong enough to choose their own path, yet born into a society that punishes choice with death. Her words, chilling and courageous, will haunt the conscience of a nation.

Sheetal’s case is tragically familiar. In a country where patriarchal traditions and tribal customs often trump legal protections, women continue to be punished—often lethally—for defying familial or societal expectations. Balochistan, in particular, remains gripped by deeply entrenched tribal honour codes that view female autonomy as an existential threat to male control.

Despite the Anti-Honor Killing Laws enacted in 2016, which closed legal loopholes that previously allowed families to “forgive” perpetrators and halt prosecutions, enforcement remains dangerously lax. The law exists on paper, but justice is rarely served—especially in rural and tribal areas where local jirgas (tribal councils) continue to settle such cases privately.

Sheetal’s murder has not gone unnoticed. Protests erupted in Turbat, Quetta, and even in some urban centres of Pakistan, led by women’s rights activists, civil society groups, and students, demanding accountability and action. Chants of “Justice for Sheetal” rang through the streets, accompanied by placards condemning the state’s failure to uphold women’s basic rights.

Human rights organizations, including the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) and Aurat March collective, issued strong statements, decrying the impunity that surrounds honour killings and the cultural acceptance that enables them. “This is not just a tragedy—it’s a national shame,” one protester declared.

Sheetal’s murder is not an anomaly, but part of a disturbing continuum. According to the HRCP, hundreds of women are killed annually in Pakistan in the name of honour—though the real numbers are likely far higher due to underreporting and societal stigma.

Some recent and chillingly similar cases include: Qandeel Baloch in 2016, the social media star strangled to death by her brother for “dishonouring” the family through her online persona. Despite initial outrage, her killer was released after serving only a few years in jail. In 2022, Afshan Latif, a young woman in rural Punjab, was burned alive by her father and uncle for marrying a man of a lower caste. In 2014, Saba Maqsood survived being shot and dumped in a canal by her family for marrying of her own will. Her case became emblematic of the failures of legal justice, as her family went unpunished.

These cases reflect a society steeped in misogyny, where female independence is policed, punished, and too often extinguished with bullets or blades. The state, despite its rhetoric, continues to fall short of ensuring protection and justice.

The murder of Sheetal is not merely a tragedy—it is a systemic failure. It reveals the deep cracks in Pakistan’s legal, cultural, and moral framework. Laws are meaningless without implementation. Outrage is hollow without reform. And justice is insulted when murderers walk free under the guise of tradition.

It must stop.

The blood of Sheetal and countless others cries out for justice. Pakistan must not allow outdated tribal codes and patriarchal honour to override human dignity and women’s fundamental rights. This is not a cultural issue—it is a crime, and it must be treated as such. If the state cannot protect its daughters, then the nation must reckon with the question: Whose honour are we really protecting?